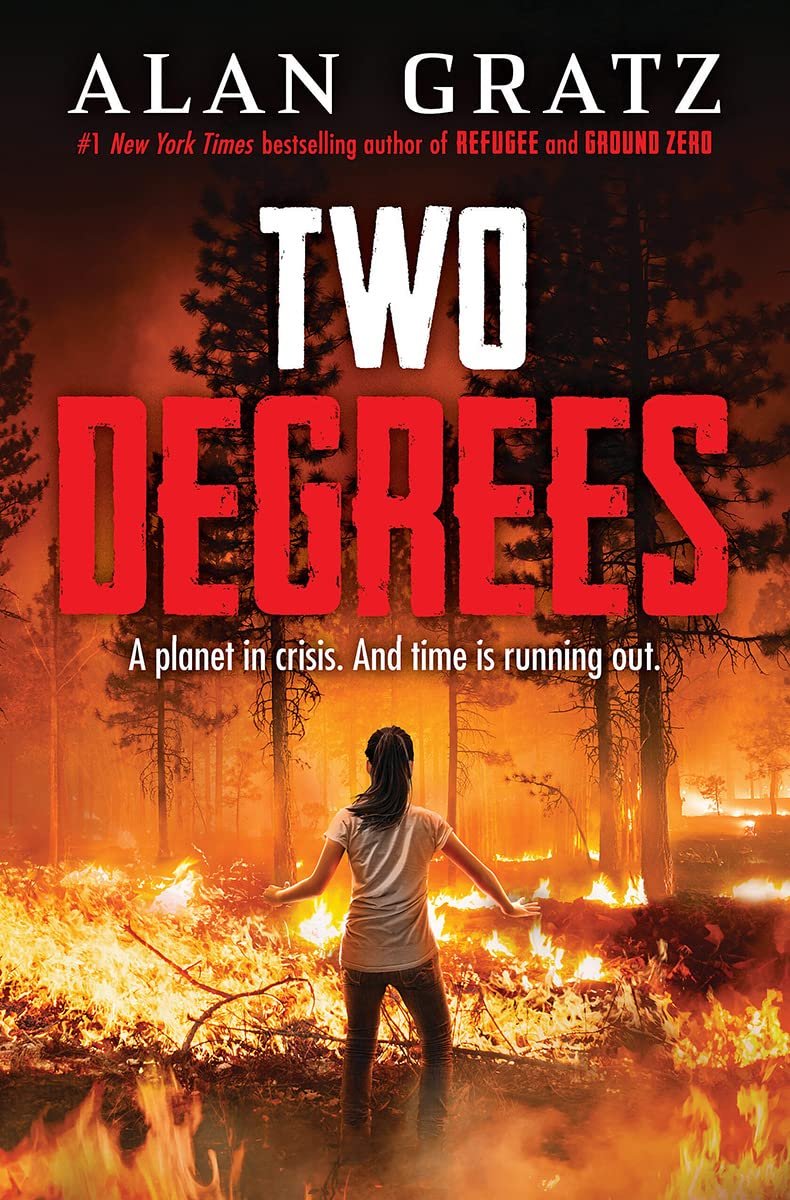

Two Degrees

Recommended Ages 9+

Caution: LGBT Characters

Typically, Alan Gratz is one of my go to authors for historical fiction. While his writing is gripping and fast paced, it also displays the harsh realities of war leaving the reader with issues and ideas to think about. Two Degrees is his first real departure from historical fiction that not only falls well short of expectations, but is a trite attempt at a complex issue. There is much that was a disappointment in this book. If you are looking for a short take away – there is better fiction out there and I would caution against the subversive messaging.

To start, the novel follows his typical style of providing multiple viewpoints. This story follows Akira in Sierra Nevada, California who is trapped in a wildfire, George and Owen in Churchill who are attacked by a polar bear, Manitoba (Canada), and Natalie Torres in Miami, Florida who is caught in a hurricane. Unfortunately, all of the characters are flat, with the exception of Owen and even then it is clearly contrived and not a natural development.

From the start, Akira is clearly at odds with her father about climate change. “Now almost every fire was a megafire that burned up half the state. And it was all thanks to human-caused climate change. Akira had learned about it in school last year, and it had scared her. But when she’d come home and told her family what she’d learned, her dad said the same thing then that he said now: ‘Nature can take care of itself’” (3). The battle between Akira and her father is a tension between their relationship throughout the novel. In Part 5 she seeks perspective of where she is in relation to the fire by climbing a tree. Akira reflects that “She felt so helpless. And so stupid. Her father had said that the earth could take care of itself...the cycle was broken...Nature wasn’t just going to fix itself. Not this time. Human beings had broken it, and it was up to human beings to fix it” (238). It comes to a head in Part 6 when she ultimately confronts her father’s “denial” of climate change in an attempt to save her family from the fire burning down her family. The tone regarding his father and his opinion regarding climate change is one of disdain and contention, that somehow her father is unintelligent and must be disregarded. “Akira hadn’t said or done anything about climate change because she didn’t want to ruin her relationship with her dad. But that wasn’t her problem, she realized now. It was his. Akira didn’t need to argue with her dad about climate change. She just needed to do what she knew was right. If her father didn’t like that, that was on him” (276). Oddly enough, desiring perspective, Gratz never develops a civil reflective conversation about the nature of forest fires and alternative views. Her father is reduced to an ignorant climate denier whom she must battle against. Another young reader's book that promotes the disrespect of parents and a further rally to battle against them is the last thing this genre of writing needs.

While George is likewise a flat character, Owen is more dynamic but only so much as it promotes the cause of climate change. The more important takeaway for Owen as a character is that he is criticized for not thinking before acting or with what is going on about him. However, he begins to not only see what is happening about him, but begins to ask questions about what he observes and begins to think about what it might all mean. Unfortunately, he settles for easy cookie cutter answers. I would like to have seen more complex development. “The big picture. That’s what he was beginning to see now. And the big picture was climate change” (208). In contrast to Owen, George is upset and dealing with the potential of having to leave Churchill due to his father’s job loss. Sadly, the story cannot simply be focused on the topic at hand, but Gratz makes subtle comments as a nod toward the LGBTQ community. On page 38 George is complaining about the lack of more girls in their school. To which the response is “Or boys, for that matter, thought Owen.” This odd comment is later followed up in the Epilogue with a comment about interviewing other speakers at a Kids for Climate Change rally. Owen wants to interview a boy from Louisiana. ‘’Uh-huh,’ said George, giving him side-eye. “Well, if you get to interview him, I get to interview the girl from Miami...’” (350). These interactions are so off compared to everything else in the story that it is clear that it is an agenda and nod being made by the intentional incorporation.

Natalie lives with her mother in Miami, Florida and enjoys tracking hurricanes focusing on the impact that climate change is having on the weather. Her room is covered with posters of storms and Greta Thunberg (59). “’Hurricanes are coming earlier and ending later...The storms are getting bigger too...and it’s all because of climate change. Burning fossil fuels puts carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which traps the earth’s heat’” (54). Natalie doesn’t battle her mother like Akira her father, but Natalie does have a pressing desire to challenge what can and should be done to battle climate change. She is a flat character who is easily swayed by an older character, Patience, whom she meets in the hurricane. It comes across more so as she is being used to help promote a cause and of course, once again, there is no critical thinking or alternative discussions. There is a clear agenda to push and no other ideas or points to add to the discussion, which is an irresponsible use of Gratz’s platform and influence. Ultimately, Natalie is the one to organize the rally that brings the characters together at the end.

This novel is so out of character with Gratz’s typical writing. There are parts that are engaging where you encounter his typical descriptive engaging writing, but it is tainted by all the obvious attempts to push an agenda that is not only preachy but breaks the narrative style and interrupts the story. Example of these instances include the following:

Akira and her dad encounter another hiking pair, Sue and her father Daniel. Daniel is concerned with climate change and challenges Akira’s dad. “’You’re kidding, right? You don’t think the huge amounts of greenhouse gases we’re releasing into the air by burning fossil fuels has anything to do with the fact that the earth keeps getting hotter?...Climate change is real, and we’re causing it” (10).

When Akira and her group reach a parking lot, the single car in the gravel in the parking lot is referred to as “a sleek-looking four door hybrid” and is compared to the heavy-duty gas-guzzling pickup truck” (13). No connection to the fact that Akira’s family has horses and a heavy-duty truck is necessary for transporting such animals.

There are several references and jokes related to weather, such as calling characters “ice holes” (34, 40, 108, 114, 222) and getting the “hail out of here” (83,90, 187, 200).

Crap is used several times on page 43.

Dead bodies are seen by the characters, either in water or burned from the fire (119, 148).

There are odd points at which racial identity is mentioned and other times it is not. Sometimes Gratz references whether someone is black or white and at other times it is simply a boy. This inconsistency is odd. Furthermore, the time he does mention that men are white, they are holding guns and trying to keep stores from being looted (310). They are contrasted with the Chinese lady who gives Natalie dog treats for the dog she carries.

Some details seem absurd at points in the story. For instance, in the middle of surviving, Natalie thinks of how one of the boys is cute (125). She also encounters a manatee in a rooftop pool (184). Akira mentions the meeting of her two best friends (referencing Sue who she met hours ago and her horse) (265). George and Owen are seriously injured and Owen has lost a lot of blood. However, they somehow manage to enter a freezing pond to keep a tranquilized polar bear from drowning (294-5).

One somewhat funny scene is the insult contest between George and Owen. However, it turns serious and is used to reveal what has been bothering George since the start of the story (167). Crap is mentioned again in reference to an insult (168).

Patience, a young adult Natalie meets, has an impact on her as well as Akira. Unfortunately, her agenda and view is likewise a simplified cliche of the oppressed victim needing to battle the government and the rich. While she seeks to rightfully help those in her community, she lacks attention to personal responsibility and simplifies a complex issue to class division and conflict. Certainly not a message I would want instilled in young readers. In response to the devastation left by the hurricane, she states “We need to have ways to evacuate people in the path of a storm who can’t afford to leave...We need to have warehouses full of emergency food and water and medical supplies in advance...we need to be working on climate change, because that’s what’s making all this worse in the first place” (252). On page 316 Patience is blaming FEMA and the government for the lack of response she is getting for the needs her organization has. On page 322 Patience responds in disgust “Glad the rich people were first on the list. Needed the power to run their juicers and exercise bikes, I guess.” This has a profound effect on Natalie as she now questions her friendship with a girl named Shannon and begins to doubt their ability to be friends because of their socio-economic differences. “Natalie couldn’t imagine her and Shannon going back to being friends when this was all over. Shannon was a nice person, but it was like the two of them lived on different planets” (323). Natalie goes on to say to a reporter “Most of those rich people, they already got out of town. But they’re still the first to get their power back...People say we’re all in the same boat with climate change, but we’re not. Some people get to ride out the storm in yachts while the rest of us are clinging to whatever floats by and trying not to drown” (329). Shannon isn’t really accepted back as a friend until her family volunteers and donates money to the cause (356). What an absurd message to include for young readers and certainly one that promotes prejudice and stereotypes.

Natalie reflects on the loss of a dear neighbor and how it was not fair for her to die in the hurricane. Stating that “No one person should suffer so much loss” (315). However, not to disregard the life or back story for this character, but she was elderly. Natalie wasn’t nearly upset about the loss of life from the woman who drowned in her car. It is the inconsistency and convenience of certain details that was such a struggle for me as I read this book.

The epilogue is the rally in which the characters all come together. It is full of messaging to encourage children to be activists for the climate change agenda.

In the Author’s Note, Gratz writes “I’ve been heartened to see young activists like Greta Thunberg take to the streets to lead protests against climate change and challenge the world’s leaders to take action” (368). This book is his attempt to boost their message.

There is so much about this book that was a disappointment, but I think the fact that it came from Alan Gratz is what aided in the level of disappointment I feel. I don’t have any issue about starting and having a conversation about climate change, but let's do so responsibly and not relegate the conversation to an either or as if the issue is simple and not complex and multifaceted. Electrical Vehicles and the process to make such has its own cost and detriments to the environment that are worthy of conversation. Solar and wind are not always viable options. There are limitations that have to be weighed against benefits and needs. To present such a complex topic and issue in such a simplified manner to push an obvious agenda and message is negligence.